The Meg – Why Megaprojects Fail

Updated:

Published:

I’m writing this blog in the depths of Covid-lockdown and Netflix is relentlessly pushing their series; The Meg.

I’m writing this blog in the depths of Covid-lockdown and Netflix is relentlessly pushing their series; The Meg.

The Meg in question is a Megalodon – a giant prehistoric shark. Ruling the seas for around 13 million years, the Meg was an absolute monster… I mean, just look at its tooth!

The Meg could chomp you down for a starter, then swallow your whole boat for a main course!

Of course, the Netflix Meg is CGI-generated. Technology has brought back to life this long-extinct monster.

There’s another kind of Meg that can chew you up just as effectively as Megalodon, if you’re not careful. The Meg in question is a megaproject.

Megaprojects go wrong, and when they go wrong, they go really badly wrong. Dr. Atif Ansar of Oxford University, explained that the average megaproject suffers from a 40% cost overrun and a 34% delay.

Moreover, according to Dr. Ansar, 1 in 10 megaprojects turns into a Black Swan – a project that simply devours time and money with, seemingly, no end. If we can understand what goes wrong, maybe we can avoid these problems and maybe we can learn something about where “normal projects” often go wrong as well.

Moreover, according to Dr. Ansar, 1 in 10 megaprojects turns into a Black Swan – a project that simply devours time and money with, seemingly, no end. If we can understand what goes wrong, maybe we can avoid these problems and maybe we can learn something about where “normal projects” often go wrong as well.

Why Megaprojects Fail

The answer to this question is not trivial, but can be summarised into 3 main themes. According to Dr. Ansar, overconfidence, strategic misrepresentation and complexity are all key factors. You can watch the whole webinar by clicking on the video, but this blog is a very brief summary and discussion.

Overconfidence: It may surprise you, but everyone involved in your project (mega or not) is human. This sad fact means that the decisions they make are influenced by over 150 different types of bias. Overconfidence bias is the one Dr. Ansar focused on; it means that people naturally tend to underestimate the risks in a project, and overestimate their ability to deliver it.

This leads, among other things, to projects being selected that simply shouldn’t see the light of day. Estimates of value and of difficulty are often wildly overoptimistic and so these projects are pre-ordained to get into trouble. However, at least this cause of project failure is “accidental,” unlike the next item.

Strategic misrepresentation: Over 500 years ago, Italian Renaissance diplomat Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli wrote his “instruction book for Kings,” The Prince:

“[Y]ou must be a great liar… a deceitful man will always find plenty who are ready to be deceived.”

Projects, and megaprojects in particular, are highly political. The power, the prestige and, possibly, the wealth of people involved in the project depends on whether or not the project goes ahead.

So they lie. They stretch the truth. Perhaps they simply don’t ask the probing questions.

They overinflate the benefits of the project. They minimize the risk and the dis-benefits.

This also goes on in non-mega projects too, of course, but it matters so much more with Megs because the numbers are so large and the scale creates scope to hide the truth. Talking of which...

Complexity: Megs are obviously HUGE – that’s what makes them MEGAprojects instead of projects. But with size comes complexity and the nature of complex systems is that the complexity is non-linear with respect to size.

Again, in English this time.

If you double the size of the project, you more than double the complexity. Megs are often hundreds or thousands of times larger (in terms of budget, at least) than “normal” projects, so imagine what that does to complexity.

This is where planning and importance of decision-making comes in. You cannot make the complexity disappear and so you have to manage the complexity and the risks as best you can.

Decision-making in megaproject selection

The first two (out of the three) ;main drivers of project failure, were about project selection and decision-making. We’ll come to the third driver of failure, complexity, in a minute.

The challenge here is that you have deliberate vested interests (“I gain something if we build this dam”), you have unintentional bias (“I’m really worried about climate change. This dam will produce enough green electricity for 100,000 homes!”) and you have systematic bias in estimation (we'll model the cost based on this other not-really-same project but once we have a data point people conflate this as a 'fact').

You can do a few things to reduce these biases.

The first thing would be to validate assumptions and estimates against a large data set of similar projects. While every road-build is different, they are all the same in essence. Leveraging data can really help (and Dr. Ansar’s company, Foresight.Works, can provide the data). This data can help highlight over-optimism biases, weak assumptions and risks so you can address them in advance.

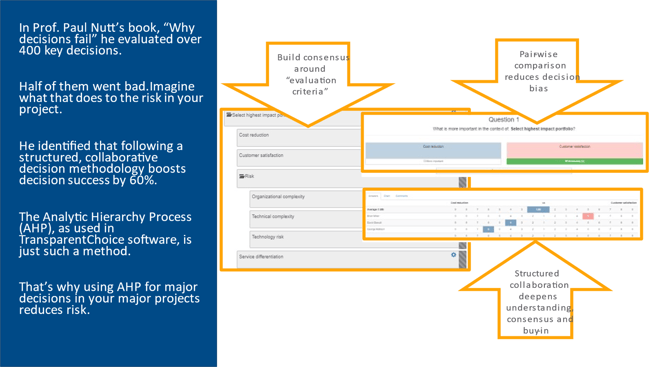

Using a suitable decision methodology such as AHP to project prioritization can reduce human bias in project selection. Getting a wide group of stakeholders to clarify what “value” actually means, and then defining the value of each potential project, helps reduce the bias or undue influence of any one individual (aka the loudest person the room) and builds alignment amongst stakeholders. It also gets past the limitation of defining 'value' as NPV (Net Present Value) by enabling a multi-dimensional set of criteria, which is likely to be key in a megaproject - just consider a road extension - that needs to balance the demands of a local economy, disruption to commuters, environmental considerations and impacted residents... to name but a few!

Our Ultimate Guide to Project Prioritization will help you make clearer, less biased decisions.

Reducing complexity-related risk: Planning

Now we get to the really messy bit – complexity.

There’s no running from this; Megs are complicated.

I was chatting online with Barry Ryan the other day. Barry is a veteran of many Megs.

I was chatting online with Barry Ryan the other day. Barry is a veteran of many Megs.

Not only has he survived, he’s thrived in a sea full of Megs.

Oddly, Barry doesn’t think that the complexity itself is why projects fail. He believes that all-too-often, the people overseeing the project simply don’t know how to set it up for success.

As an example, he says, “Usually, everyone is in a rush to start. This embeds latent risk in the project. Down the line, this greatly influences the likely outcome both in terms of cost and time. As a result, neither the project delivery strategy nor the work breakdown structure is well established”

In other words, when you mix our old friend, overconfidence bias, with poor planning, the result is pretty much guaranteed: disaster.

The Meg’s comin’ to get ya! (Cue Jaws music…)

Reducing complexity-related risk: Decision Making

But planning alone is not enough. The next area to look at is “decision-making”.

The trajectory of your project is, to a large extent, governed by the decisions you make. Here are just a few examples of decisions that can make-or-break your project:

- Which project should I do?

- Where should I build it?

- Who should build it?

- What design makes sense?

- What technologies should I use?

What’s common to all of these decisions is that they represent a large decision that is difficult to “undo” later, they have a big impact on the project and, crucially, there are multiple stakeholders.

Consider, for example, the decision of where to build an airport. We helped make a couple of these decisions a while ago. The consultant leading the decision shared their “usual process,” which went something like this;

- Run a public consultation for 6 months

- Totally fail to converge on an answer

- Pull three or four people into a room and “just make a decision”

- Announce the decision

- Get sued… and delay the project while it works its way through the courts

When they used TransparentChoice (and the AHP decision-making process that’s embedded in the software), the process took a day (okay, there was still quite a bit of procedural stuff that had to be done, but the decision was effectively made in a day).

What’s even more important is that the decision was made with very structured input from key stakeholders in the project (residents, businesses, environmental groups, etc.). This structure, that flows directly from the AHP methodology, helps reduce bias and build stakeholder support.

So the decision was made incredibly quickly and there was no lawsuit.

Here’s another example. As part of an overhaul of a transit system, a team in Sweden had to make a $200m technology selection decision. This would normally have been a 2-3 month process, but with AHP, it was completed in 3 weeks. Not only that, but it was a very robust decision that enjoyed strong stakeholder support. You can hear the story in this video.

Rapid, high-quality decisions, ones that involve key stakeholders, can speed up your project and dramatically reduce the complexity-related risk.

Maybe the Meg isn’t going to get you after all…

Reducing complexity-related risk: Predictive Governance

So, we’ve picked the right project based on the right data, we’ve made great decisions quickly and now we’re implementing.

We have Gannt charts plastered all over the walls, we understand and are tracking all our interdependencies (because we did the planning properly)… what can possibly go wrong?

The answer is, plenty.

The challenge is that there’s a lot going on. Small mistakes and errors can accumulate. Individually, all the parts of the project might look like they are “green, green, green” then suddenly everything goes yellow and then – uh oh! – red!

It can be hard to spot the systemic drivers of projects going wobbly. Part of the problem is that PPM tools are a little like the rear-view mirror in your car. They tell you where you’ve been. That can be helpful, but we really need to see where we’re going, what’s in front of us!

Luckily, there is a lot of data that flows around a Meg. Invoices, delivery notes, etc. They can all help us work out what’s going on… if only we could “read the signs”.

This is where we come back around to Dr. Atif Ansar. He has set up a company, Foresight.works, that uses AI to mine project data. It helps to identify problems before they come up. Their experience over many projects helps the algorithm make better predictions and data is the key.

What’s interesting here is that, just like the Netflix Meg, it’s technology might just prevent the extinction of your Megaproject.